Imagine a pond. Clear and blue, or blue-ish. A calm, wide spot in a creek that carries fresh snow melt straight from the mountain’s peak over smooth, oval rocks, splashing a soothing background soundtrack. A pond surrounded by cattails and reeds that nod in a whispering breeze. This is not like our pond at all.

Our pond is murky at best, usually brackish. At its worst, at the tail-end of a fiery summer of drought, it is merely a muddy swamp festering at the bottom of a shallow depression. It is not fed by an upbeat little brook or a mysterious underground aquifer. It’s just a collection site for rainwater when the surrounding dirt has had all it can absorb.

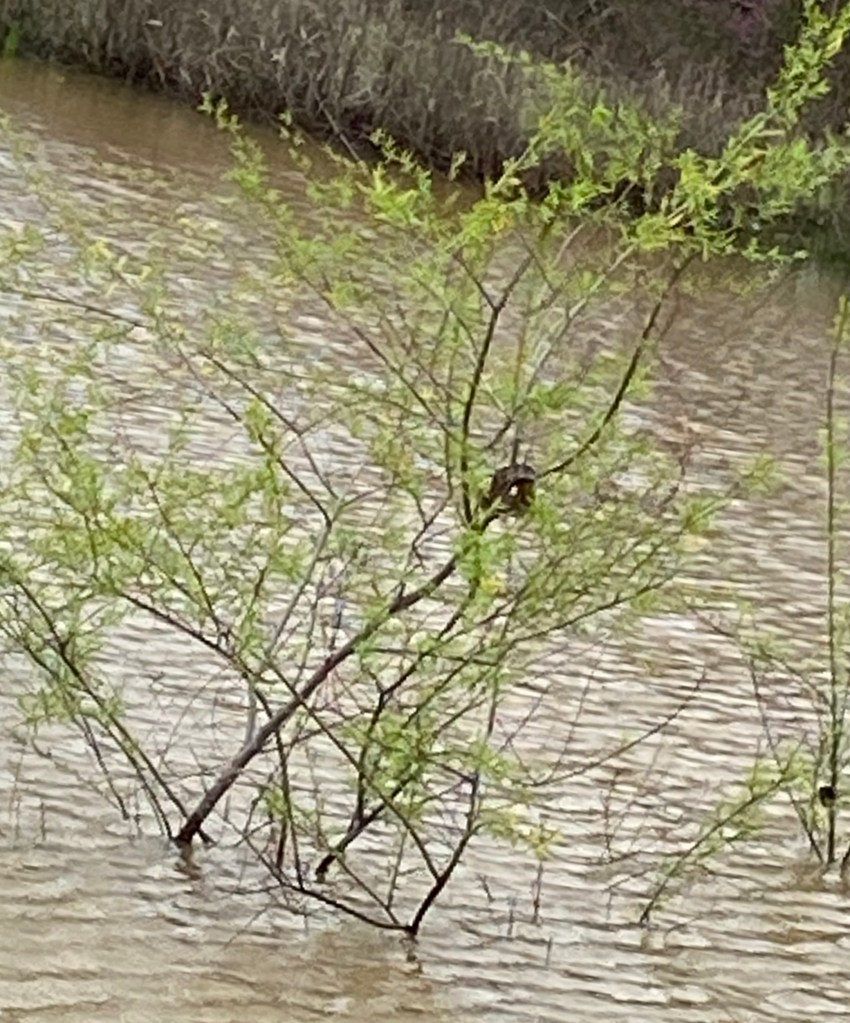

Some mature post oak trees near the shore help beautify the setting somewhat. Counteracting the gentrification efforts of the oaks are two spindly bush-like trees growing in the pond, near the middle. They are easily more than half-submerged when the pond is full. The horrid snakes who frequent the area swim out and twine their way up the branches to bake in the sun–until they are sighted and shot at. This prompts the snakes to drop back in the water, poking their heads out after a minute to enjoy a laugh at the shooter’s expense.

Humans in their right minds are not tempted to dip even a toe into the pond, but many others besides the snakes enjoy swimming there–turtles, surface-skimming water bugs, tadpoles and their cooler older brothers, the frogs. Mosquito larvae also wriggle their childhoods away in the water, and this is why a friend suggested we add some goldfish from the bait shop to the pond. You know–to eat the larval skeeters.

Living in our little pond would be scummy, but it would have to be better than a career spent as a bait fish. And so, one April Saturday, we bought a dozen goldfish from the minnow tank at the OneStop, a local convenience store and dine-in restaurant. They were released into the pond, and the next day I saw only three of them. As days passed, I saw none at all, and figured that the turtles snapped them all up for snacks. I hated the fact that twelve fish had paid with their lives for my stupidity, and promised myself that we would never stock the pond again.

In early June, a visiting offspring swore he saw a flash of goldfish gold in the pond, and a week or two later, I spotted a few flashes myself. My best guess was that we had been able to retain between four and six fish after all–still a 50% casualty rate, but not the total massacre I had feared. By July, their survival was official; approximately twenty goldfish were swimming about. They were most often spotted in the middle of the pond, in two small schools. I hoped they were learning to eat mosquito larvae and to avoid the heron that had started to frequent the banks of their watery campus.

Summer wore on with sweltering days and no rain. The pond’s water level dropped quickly until it was within a couple of weeks of drying up entirely. I was unable to embrace a “live and let die” policy as far as the goldfish were concerned, and I spent odd moments hatching plans to capture whatever fish were left and then transfer them to a more reliably liquid environment. Thankfully, autumn rains fell before the pond dried out completely, but the fish had vanished. Sigh. I didn’t go up by the pond much because it was just a sad reminder of our failed fish experiment. We celebrated Thanksgiving and Christmas anyway, however.

Since our lives were just too carefree and uncomplicated, we adopted a dog in January. On one of our very first walks, I was surprised and delighted to see four orange circles in the pond–four separate little gatherings of goldfish! There were easily one hundred fish milling about. Talk about making a comeback! Of course, the heron came back, too, as well as the fishing feral cats, but still!

We imagined the fishy come-ons that were floated during the last few days of that summer drought:

“There’s a water shortage, time is getting late. I’m feeling kinda frisky– girlfriend, let’s don’t wait!”

“You and me, baby. There’s still water. Let’s make (fertilized) eggs!”

“We’ll probably all die anyway. Why not go out with a bang?”

Obviously, there’s a great lesson here about not giving up. About persisting despite overwhelming odds. About stocking up on eggs, because hey, you never know. For me, though, I think the takeaway is that I have no business having farm animals of any kind.